Artwork

Nature

Caravaggio’s assertion that painting fruit or flowers required as much effort as depicting human figures challenged the artistic hierarchy of his time. During the Catholic Counter-Reformation, sacred art focused on Biblical themes, while still life subjects—“Natura Morta”—were considered inferior. Caravaggio’s meticulous rendering of a fruit basket elevated the mundane to the sacred, pioneering the still life genre and reshaping Western art. His radical realism and dramatic chiaroscuro revealed emotional and spiritual depth in everyday subjects, a style later termed Luminism by Roberto Longhi.

This reverence for nature resonates with the Japanese tradition, where leaves and humble flowers symbolize impermanence and the vanity of material existence. The artist finds deeper meaning in portraying these quiet elements, aligning with the Western concept of memento mori—a reminder of mortality. Similarly, Dutch Golden Age painters used symbolic still lifes to reflect life’s transience.

Painting leaves and flowers becomes a cross-cultural meditation on fragility, dignity, and illumination. It is not merely a study of form, but a philosophical dialogue with artistic masters across time and geography. Through this lens, nature’s overlooked details become profound expressions of mortality and spiritual truth, bridging Eastern and Western sensibilities in a contemplative act of creation.

Life-Scape

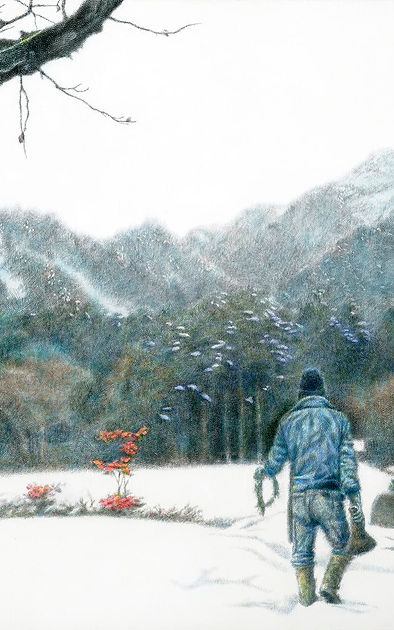

Life-Scape is my response to the evolving relationship between humanity and nature. I often ask whether any realm—physical or intellectual—remains untouched by human influence. The Industrial Revolution reshaped the world, and its legacy of faith in science and technology persists today, forming a near-global belief system. As we enter the Fourth Industrial Revolution, driven by Artificial Intelligence, I feel compelled to reclaim narrative through visual language.

I gather the daily lives of people, rooted in their unique histories and cultures, and weave them into new stories—not mere landscapes or photographic reproductions, but post-21st-century inquiries into meaning. Inspired by Jean-François Lyotard’s idea of the “grand narrative,” I wonder whether AI itself might become a new system of belief. Yet I find deeper resonance in the life of Morikazu Kumagai, a Japanese painter who saw the cosmos in his garden. His quiet devotion to nature reveals a realm of expression forever beyond algorithmic reach.

Through my technique—sumi ink and acrylic in intricate line-hatching—I pursue what Umberto Eco called the “open work,” rich in layered meaning and open to interpretation. In crystallising the present moment, I aim to evoke the enduring pulse of human life. This is the essence of the Life-Scape I strive to create.

Portrait

Portraiture has long stood as a potent emblem of authority and reverence, historically serving to exalt rulers in near-divine terms. Yet over centuries, its form has undergone profound metamorphoses, acquiring layered meanings and diverse modes of expression. The emergence of photography, in particular, disrupted painting’s primacy in portraiture, prompting artists to seek new expressive pathways and heralding a shift toward abstraction and contemporary art. Still, the core essence of portraiture endures: it represents the subject, explores their inner self, and is anchored in the relational dynamic between artist, sitter, and often, the commissioner.

This complexity is embodied in L. S. Lowry’s self-portrait—a stark spire rising from a grey sea, devoid of human likeness yet rich in solitude and integrity. Its absence of physical representation invites reflection: Can a portrait exist without a visible subject? My own practice—painting fallen leaves and wildflowers as symbols of unnamed, suffering individuals—suggests that portraiture may extend beyond literal depiction to evoke shared human fragility and dignity.

Such inquiries probe the very nature of visual representation: the space between seeing and being seen, illusion and truth, body and spirit, existence and absence. In this light, portraiture becomes not a fixed form, but a boundless field of poetic possibility.

Japanesque

Japanese traditional art first captivated the West during the mid-19th-century Paris Expo, where ukiyo-e prints used as wrapping paper sparked a wave of Japonism among French impressionists and beyond. As a Japanese artist living in the UK, I feel a deep emotional connection to Japanese culture. I see Western art as rooted in meta-narratives and theoretical reinvention, while Japanese art evolved in isolation, shaped by centuries of samurai rule and cultural seclusion. This history fostered an aesthetic focused on surface beauty, nature, and historical motifs, deliberately avoiding philosophical speculation. Such beauty, fragile yet profound, resonates with the Western concept of memento mori.

Among all creatures endowed with the faculty of sight, it is only humankind that possesses the singular awareness that the act of seeing is performed by the self. This self-reflective gaze does not indiscriminately absorb the world; rather, it selects consciously what it wishes to behold. This transformation of desire into visual expression lies at the heart of Japanese aesthetics. Its minimalism and depth once inspired the West and continue to influence global culture through manga and anime, which blend Western methodologies with Japanese sensibilities. Ultimately, I seek to reframe the Japanesque—not as nostalgia, but as a vital inquiry into contemporary art’s direction, honouring tradition while engaging with the future.

Drawing in Colour

Here I assembled a variety of drawings in colour. Oil, for instance. It is the principal technique that has become dominant throughout art history up to this day, since Flemish school masters typified by Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden established this great art practice in the 15th century. As countless artists explored new expressions and techniques with this medium, I feel unable to contribute anything. Hence, a handful of my oil sketches before shifting to explore a new method using Japanese sumi ink & acrylic. In another instance, to explore the concept inspired by the Baroque musical genius Johann Sebastian Bach, I experimented with drawings in different textures, techniques and patterns in a specific arrangement as if it were a musical composition. Bach’s creative process was deeply rooted in his Christian faith. He used religious symbolic numbers in his musical compositions. 2D art is, however, categorised into spatial art. I wanted to make it as if it could be time art, in other words, "art based on tempo" such as literature, music and cinema. Carefully arranging each image by symbolic numbers, I tried to compose some core patterns of human experience relating to my personal life. Recent drawings tend to be preparatory to gain precision in composition to draw deep emotions, intellectual and psychological states, and subtle nuances of a person in question.

Drawing in Monochrome

As for me, pencil drawing is always my favourite practice in all art forms since my childhood. It is so simple that even an infant can do it, yet it’s often so demanding…, certainly it’s nothing less than drawing that requires of all artists a great skill to observe, understand and depict things as they are. It is not easy. Needless to say, it is the most fundamental skill in all art practices. I always recall myself enjoying drawing with twigs and pebbles on the ground in my early childhood before I was given pencils and notebooks. Looking back, it was always autumn for me to launch a new thing or turn to a new direction. Then, in the course of time, my conceptual drawing series "Autumn Leaves" was born. Since then, I‘ve been exploring how to enhance this concept in drawing. Talking about autumn leaves, for instance, they are nothing but the object fallen into decay, yet that is why they are totally "open" to viewers as if Vincent Van Gogh firstly introduced this concept when he painted "a pair of boots"; which provided the platform for Martin Heidegger's philosophical debates.

Here I assembled my drawings in monochrome, mostly those with graphite pencil and some with watercolour.